Tormented Territory: The Emergence of a De Facto Canton in Northwestern Syria

- OCTOBER 03, 2023

- PAPER

Source: Getty

Summary: Northwestern Syria is being consolidated into an effective canton protected and sustained by—and dependent on—Türkiye. Given the lack of prospects for any side to secure a decisive victory in the Syrian war or for a political settlement, the territory is the outcome of conflict management processes pursued by Türkiye, Russia, Iran, and the Syrian regime since 2016.

SUMMARY

Syria’s northwest has been progressively transformed into a de facto canton outside the control of the Syrian state. This is the outcome of a dynamic process that began in 2016 and that mainly reflected the security interests of Türkiye, Russia, Iran, and the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. This framework, which has been an alternative form of conflict management, has allowed these actors to systematically adjust the canton’s characteristics, a painful process that is ongoing.

Armenak Tokmajyan

Armenak Tokmajyan is a nonresident scholar at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. His research focuses on borders and conflict, Syrian refugees, and state-society relations in Syria.

KEY THEMES

The characteristics of the canton is that it is a territory beyond the control of the Syrian state, functioning within a Turkish supranational security framework, sustaining itself through political and economic ties with Ankara, and having a population Syria’s leadership had no desire or ability to reintegrate into Syria.

After Russia’s intervention in 2015, Syrian government forces went on the offensive, regaining territory, so that what remained of Syria’s conflict was concentrated in the northern border area where the canton has emerged.

A critical juncture in northwestern Syria’s transformation into a canton began in 2016, when Syrian government forces and their allies recaptured eastern Aleppo city and Türkiye launched its first military incursion into Syria.

A consequence of the Syrian government’s victories was that 200,000 people were evicted to what would become the northwest canton, consolidating its distinctive Sunni rural sociopolitical outlook, one uncompromisingly hostile to the regime.

Decisions reached in bilateral meetings, particularly between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and in multilateral formats, such as the Astana process, served as platforms for reaching mutual agreements over Syria, altering the country’s northwest.

FINDINGS

The effective cantonization of northwestern Syria could be seen as an alternative form of conflict management. It was a response to a Syrian war that had no prospects either of seeing a decisive victor or reaching a political settlement.

The ongoing process of cantonization derives from Russia, Türkiye, Iran, and the Syrian regime’s constantly adjusting northwestern Syria’s security-related, demographic, economic, and political dimensions in accordance with their interests.

The adjustments to the canton are likely to continue because none of the four countries involved in northwestern Syria is content with the present situation, while communication among them has increased.

By and large, the adjustments witnessed in the northwest since 2016 have been marked by immense pain and hardship—encompassing war, securitization, mass displacement, thwarted rebellions, demographic shifts, and intense competition over limited resources. If further adjustments take place, it is improbable they would be any less distressing, with civilians bearing the heaviest toll.

INTRODUCTION

Russia’s military intervention in Syria in September 2015 on the side of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime led to a critical turning point in the country’s conflict the following year. It put an end to aspirations among Assad’s foes, domestic and foreign, to bring about a change of regime. The intervention also fundamentally altered the regime’s relationship with its own national space and demographics. Up until then, Syria’s leadership and its supporters were focused primarily on defending territory. With Russia’s aid, however, government forces and their allies went on the offensive and captured opposition strongholds one after the other in central and southern Syria. By summer 2018, when the regime recaptured Syria’s south, what remained of the conflict was concentrated in the northern border area with Türkiye.

Russia’s intervention was also a watershed in transforming Syria’s opposition-held northwest into what is effectively a canton. The region became an autonomous territory outside the control of the central Syrian authorities, with its survival depending on cross-border political and economic links, tied to a supranational Turkish security framework, and whose population the regime had no desire or ability to reintegrate into the state structure. Having abandoned its efforts to overthrow Assad, Türkiye, in agreement with Russia, adopted a much more hands-on approach in Syria. In 2016, it launched the first of several military incursions there and expanded its security and economic presence in Syria’s northwest. The Assad regime, in turn, recaptured opposition-held areas of Aleppo city toward the end of 2016, after Ankara withdrew its backing for local rebels. That this resulted from an under-the-table Turkish-Russian agreement represented the first milestone in northwestern Syria’s transformation into a canton.

Increasingly, this canton became an integral part of Türkiye’s border security framework. Ankara, not Damascus, turned into the political center for the northwest. The canton hosted some 4.5 million Syrians, about half of them internally displaced people, while Türkiye refused to take in more as refugees. This population, with no means to emigrate, was governed by locally established, mainly civilian institutions and was highly dependent on foreign assistance. Politically, the area encapsulated the remnants of the anti-Assad political undertaking, its fate now tied to Turkish decisions. Economically, the area was sustainable only because of the Turkish border, through which goods and humanitarian aid entered.

The transformation of the northwest into a canton was the result of a complex process. The conflict in Syria and the circumstances it created were its main drivers, but so too were the practices that local and foreign actors adopted to deal with the intricacies of the war. These practices, which were implemented unilaterally, bilaterally (most notably by Russia and Türkiye), or collectively (through the Astana process, which included Russia, Türkiye, and Iran), not only contributed to the northwest’s cantonization, but also pushed the region into a cycle of difficult adjustments that included territorial, demographic, and economic changes.

The effective cantonization of northwestern Syria, like the adjustments to the canton, could also be seen as an alternative form of conflict management. It was a response to a conflict that had neither a decisive victor nor any prospect of reaching a political settlement. Cantonization was a provisional solution to a host of socioeconomic, demographic, and security realities that imposed themselves on all parties in the conflict. It did not aim to address the underlying grievances that had led to the uprising in 2011. Rather, it merely bought time, but also provided a framework in which influential actors—especially the Assad regime, Russia, Türkiye, and Iran—could adjust the contours of the canton’s boundaries according to their interests throughout the war. Increasingly in later years, they began doing so through mutual bargaining, at the expense of weaker political players in the canton.

THE PATH TOWARD AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH: CONTEXTUALIZING CANTONIZATION

After the Russian military intervention in 2015, the Syrian conflict failed to produce a decisive victor or a successful peace process, particularly the one defined in Geneva under United Nations auspices. At this time, Russia, Türkiye, Iran, and the Syrian regime adopted new approaches, each pursuing separate objectives. Among the early steps were Türkiye’s first incursion into northwestern Syria in August 2016 in the so-called Euphrates Shield operation, followed by the Syrian regime’s recapture of Aleppo city in December 2016 with Russia’s help and the formation of the Astana peace process for Syria by Russia, Türkiye, and Iran in January 2017. These dynamics led to security, economic, and sociodemographic arrangements that largely impacted Syria’s border area with Türkiye.

The Syrian uprising, which began in March 2011 and evolved into a full-fledged civil war by mid-2012, represented an unprecedented challenge to the Assad regime’s domination. Against a backdrop of the increased militarization of the conflict in 2012, the more organized, foreign-supported rebel groups began holding on to territories they had captured. The regime, in turn, gradually ceded large areas to its opponents and shifted its strategy from attempting to recapture land to consolidating its forces in strategic locations, retaining the latitude to retake territory in counteroffensives and cut supply lines. This was true especially along the north-south axis around Damascus and in the highlands near Lebanon.1

Border areas were Assad’s weak points and launchpads for the armed rebellion. By summer 2012, the regime had lost control of the borderlands with Türkiye, including the three most important border crossings—Bab al-Hawa, west of Aleppo; Bab al-Salam, north of Aleppo; and Jarablus, further east near the Euphrates River.2 Between 2012 and 2015, the regime sustained major territorial losses in the northwest, and the most it could do was to protect the western half of Aleppo city (after it had ceded the eastern half to the rebels in 2012) and fight to keep a narrow supply line open between central Syria and Aleppo, which was often disrupted by rebels.3 In contrast, by summer 2015, mostly radical rebels, supported chiefly by Türkiye and Qatar, came to control what some named “greater Idlib,” which included Idlib Governorate and portions of northern Hama and southwestern Aleppo Governorates.4

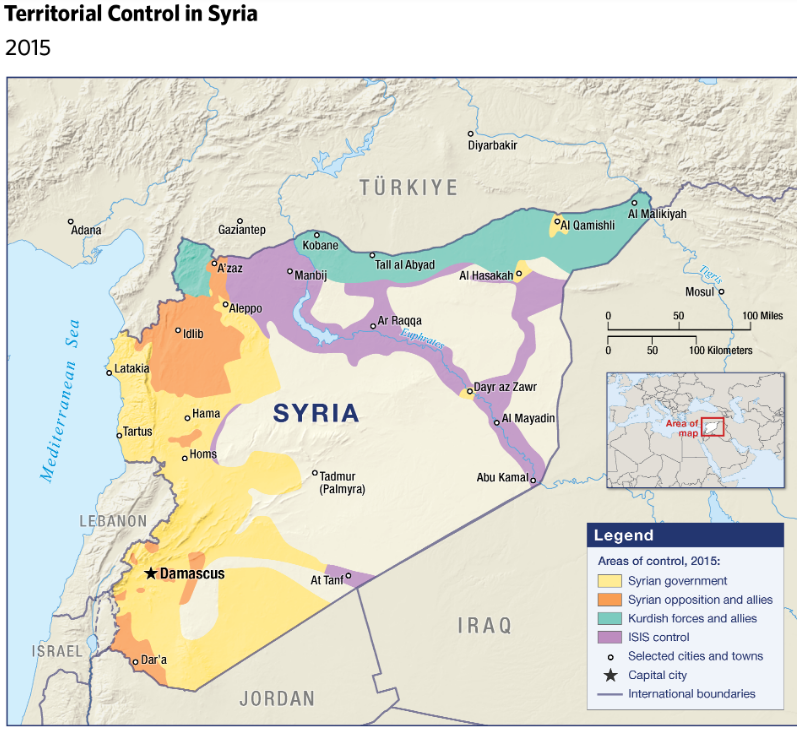

In mid-2015, there was what can be described as a dynamic stalemate in Syria. Although battles raged on many fronts, no one side was close to concluding the war in its favor. The so-called Islamic State group was fighting against the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast and against rebel groups in the north and dominated the northeastern half of Syria, while the regime held on to parts of Aleppo city and patches of isolated territory.5 The opposition had made significant progress in Idlib by capturing Idlib city, Ariha, and Jisr al-Shoughour, while it had lost most of the Qalamoun highlands.6 As for southern Syria, the front lines had changed marginally, with the exception of Jabhat al-Nusra’s capture of the Nassib crossing with Jordan in April 2015.7 The Russian intervention in September 2015 broke this wide-ranging stalemate and altered the course of the Syrian conflict.

Russia’s intervention shifted the Syrian dynamics in several important ways that were instrumental in bringing about the cantonization of the northwest. First, it put an end to the regime-change project pursued by most rebel groups and backed by external parties. Foreign support, essential for all armed groups, had already dwindled by that time, but Russia’s intervention was a turning point. The United States had stopped many of its support programs, which were focused on fighting the Islamic State with its principal local partner, the SDF, whose backbone is the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which is closely tied to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, in Türkiye.8 Key Arab countries, namely Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Jordan, also terminated major assistance to rebel groups, while Qatar continued its support, though exclusively through Türkiye’s military and security institutions.9 Ankara, in turn, monopolized military support in the northwest.

Second, with no political or military support for the armed opposition groups, except in the north, the Assad regime, bolstered by Russia and other allies, recaptured rebel-held areas throughout Syria.10 Syrian government forces came to dominate the battle space on a large scale for the first time since the beginning of the conflict. Until then, the regime’s only major success had been in Qalamoun, where between 2013 and 2016 it recaptured the area and cut supply lines from Lebanon, thanks to extensive assistance from Hezbollah and Iran.11 The new reality fundamentally transformed the control map of Syria and, beginning in 2016, limited the conflict to the country’s northern borderland with Türkiye.

Third, Russia’s intervention had a strong impact on Türkiye’s approach toward Syria. Ankara’s involvement in the conflict, especially in the northwest, whether as a host to refugees, a facilitator, or a supplier of humanitarian or military aid to armed groups, began very early in the conflict. During the first few years of the war, Türkiye overtly sought to topple Assad’s rule by means that allegedly included support for extremist groups.12 Ankara also encouraged Washington to lead an effort to create a safe zone in the north, which could presumably be turned into Syria’s version of Benghazi in Libya, from where the rebels could go on to capture Damascus.13 Nonetheless, Türkiye remained more a cross-border launchpad for such activities than their architect.14

Starting at least from 2014, after the Syrian regime showed unexpected resilience and Washington shifted its focus to defeating the Islamic State,15 Ankara began adopting a more hands-on attitude. It sought greater control over cross-border humanitarian and military activities from its territory.16 The Russian intervention accelerated this Turkish policy direction. Perhaps more importantly, Türkiye also found in Russia a partner to end the Syrian conflict. Moscow was a difficult partner, to say the least, but it was ready to tackle the complex issues the war had engendered. This came at a time of very strained U.S.-Turkish relations.17 While the reasons for this were not exclusively tied to Syria, in the Syrian context Ankara opposed Washington’s backing of the SDF, which it sees as an extension of its archenemy the PKK.18 Türkiye’s fear was that a reinforcement of Kurdish groups in Syria might lay the foundations for a PKK-affiliated Kurdish autonomy project in Syria.19

On the political front, Russia’s intervention had the practical impact of marginalizing the UN peace process for Syria that was launched in Geneva in December 2015, with passage of Security Council Resolution 2254.20 The resolution called for a “Syrian-led” political transition and agreement on a new constitution, followed by UN-supervised free and fair Syrian elections under the new constitution, among other things. Moscow never indicated that it intended to undermine the UN process, which hardly had any chance of success. 21 However, its intervention altered the military balance in such a way that there was no incentive for the Assad regime to make any of the concessions implicit in Resolution 2254.

Furthermore, Russia, along with Türkiye and Iran, initiated a parallel process to the UN’s in January 2017, that would become the Astana track.22 Like the Geneva process, the political dimension of the track hardly achieved anything. On the ground, however, the three players, with the indirect involvement of the Syrian regime, changed the course of the conflict. The trio formalized the rationale of negotiating among themselves in a way that reshaped the war. The Astana process did not seek a just solution for Syria, but provided a platform that increasingly excluded Western actors; restricted the war to Türkiye, Russia, and Iran, with the Assad regime; and sought to end the status quo.

By 2016–2017, the situation in northwestern Syria had become a problem for several major political actors. Türkiye was hosting 2.5 to 3 million Syrian refugees and could not absorb any more.23 Extremist groups in Syria posed a further problem, and Türkiye was not spared terrorist actions.24 The Kurds, Ankara’s chief security problem, controlled most of the Syrian-Turkish border and were on their way to forming a state within a state.25 The Assad regime, in turn, was equally unhappy with the status quo. Emboldened by Russian support, it sought to recapture as much territory as possible, prevent a Kurdish statelet in Syria’s rich northeast, marginalize the rebels in the northwest, and secure a Turkish withdrawal from Syrian territory. That is why the Astana process emerged as the most viable platform for Russia, Türkiye, Iran, and the Syrian regime to settle their disagreements. This is the context in which the cantonization of the northwest took place.

CANTONIZATION OF THE NORTHWEST AS AN INTERIM SOLUTION

The first step in the cantonization of the northwest came in late 2016, when regime forces attacked and recaptured all of Aleppo city and Türkiye launched its Euphrates Shield operation. Subsequent Turkish interventions put large parts of Syria’s northwestern border areas outside the reach of Syrian government forces, facilitating the conditions for the subsequent emergence of a canton.

Generally in Syria, four factors characterized the canton. First, the northwest became more entrenched in Türkiye’s supranational security framework focused on the border area with Syria. Second, politics in the canton were defined largely by Turkish priorities. Third, the northwest became a haven for 4.5 million Syrians, many of them opponents of the Assad regime with their social base. And fourth, economically, the region became more dependent than ever on the Turkish border for commerce and humanitarian aid.

These four characteristics became more ingrained over time through adjustments to the canton. Starting in 2016, the northwest underwent a mostly painful process carried out by Russia, Türkiye, Iran, and the Assad regime to reshape the canton militarily, economically, and socially. This brought about major changes in terms of control and caused significant military and civilian casualties. It also triggered massive population displacement and greatly altered the region’s prewar sociopolitical and socioeconomic characteristics, reflecting Russian, Turkish, Iranian, and Syrian regime priorities.

PART OF A SUPRANATIONAL SECURITY FRAMEWORK

The northwest remains part of Syria, without any stated aspirations of autonomy or separation. Nevertheless, since 2016, and more so today, the northwest’s detachment from other parts of Syria has only increased amid a lack of any viable national framework to reunite it with the rest of the country. Instead, the region has effectively become more integrated into Türkiye’s border security framework and, in its current form, can exist only in that framework. The northwest evolved from being one of the Syrian uprising’s hot spots into a bastion of armed rebellion against the political center, Damascus, only to be transformed, as of 2016, into a buffer zone protected by the Turkish armed forces. The areas the regime recaptured after Russia’s intervention—eastern Ghouta near Damascus and southern Syria, for example—were reintegrated into regime-controlled Syria.26 Damascus again became the political center. In contrast, the northwest was integrated first and foremost into Türkiye’s security architecture on its southern border, primarily as a counterweight to the U.S.-backed Kurdish forces to the east. Ankara became the region’s political center.

A chain of interrelated events in the latter part of 2016 in the northwest embodied the turning point toward cantonization and reflected the new dynamics at play. This came after the regime had engaged in a prolonged multifront offensive around Aleppo the year before and retaken territory from rebels in northern, southern, and southwestern Syria, and from the Islamic State in the east.27 Syrian government forces launched their final assault on rebel-held Aleppo in September 2016 and fully captured it by the end of year.28 At the time, Türkiye, alarmed by the SDF and wider Kurdish gains in the north, reached a surreptitious arrangement with Russia.29 Russia would not oppose a direct Turkish military intervention in northern Syria to push back against the SDF, while Türkiye, in response, would end its backing for the rebels in the eastern half of Aleppo city.30

However, outside Aleppo, Syrian rebels, supported by the Turkish army, occupied an area extending from the eastern boundaries of Kurdish-dominated Afrin, north of Aleppo, all the way to Jarablus and Al-Bab in the east.31 With that, they prevented uninterrupted Kurdish control of the border from Manbij to Afrin and deterred the Islamic State, which was also present in the area. At its core, this Turkish-Russian bargain epitomized the end of the armed rebellion to topple the regime, nullifying the opposition’s raison d’être, and essentially divided Syria’s northwest between the Assad regime and Turkish forces.

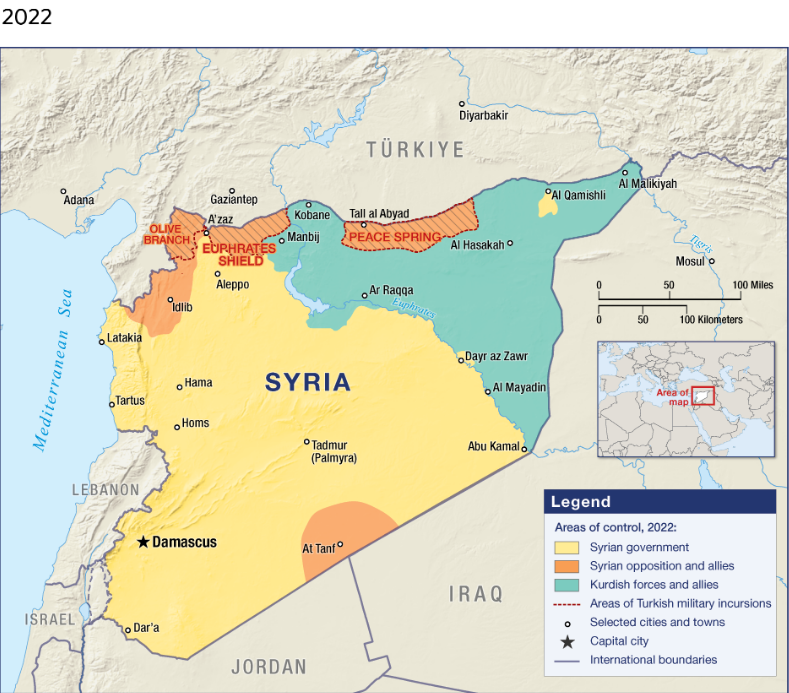

This was the most essential step in cantonization. No feasible national framework was available for Damascus to reintegrate northwestern regions into Syria proper. In contrast, these areas were now part of a Turkish security framework and, unlike the situation prior to 2016, could no longer exist outside this framework. Afrin’s fate illustrated the dire nature of the adjustments taking place, and even more the incorporation of these areas into Türkiye’s security architecture. In conjunction with Russia, whose military police withdrew from Afrin in January 2018,32 Türkiye and its local proxies captured the area and ended the rule of the Democratic Union Party and the YPG, both affiliates of the PKK.

In Idlib, however, Türkiye never exerted the firm control it did in the areas it had occupied militarily. Nonetheless, after Aleppo was retaken by Syrian government forces, Idlib also gradually became integrated into Türkiye’s security architecture. Those areas were subjected to painful adjustments as well, and to an increased Turkish military presence, thanks to the Astana process. On September 15, 2017, Russia, Türkiye, and Iran, working through Astana, established observation points along the military line of contact in Idlib Governorate and its vicinity. 33 According to a statement by the participants, the observation points would dot the front line from both sides to “prevent the occurrence of hostilities,” which would be necessary for reaching a political settlement in Syria.34

At first, one of the major anti-regime armed groups in Idlib, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, resisted Türkiye’s greater military presence in the area, but could do little to prevent it.35 Within months, Türkiye had established twelve points on the side controlled by the opposition, across from ten observation points by the regime’s allies, Russia and Iran.36 In practice the observation posts marked the boundaries between areas controlled by Syrian government forces and the canton under Turkish protection.

Another milestone in the adjustment of the northwest canton occurred after a meeting in Sochi between Putin and Erdoğan in September 2018. The two leaders agreed to establish a 15–20-kilometer-deep demilitarized zone along the front line, within opposition-held areas.37 “Radical elements” would withdraw from the area, while more “moderate” rebels would be allowed to remain, though without heavy weaponry.38 This top-down adjustment in opposition-held Idlib faced fierce resistance from some rebel groups, especially Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, and was hardly implemented. Despite the Sochi agreement, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, a Salafi-jihadi movement that emerged during the war as an alternative to the regime and for a time was al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria,39 retained control over the area that was supposed to be a demilitarized, including sections of the strategic M4 and M5 highways.40 All this took place as tit-for-tat attacks between government forces and rebels escalated.41

When the deal failed to materialize, the Syrian military, supported by its allies, launched a multiphase offensive against the rebels in Idlib, above all Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham.42 By the end of August 2019, the regime had captured northern parts of Hama Governorate, which was followed by a ceasefire and an attempt to revive the demilitarized zone. When this effort again faltered, in December government forces renewed their offensive and made significant advances in eastern and southeastern Aleppo Governorate, recapturing the M5 highway.43 Only direct intervention by Türkiye on February 27, 2020, and a subsequent ceasefire agreement reached by Ankara and Moscow halted the offensive.44

The episode, Ankara’s intervention in particular, highlighted a number of important factors that only reinforced the notion that Idlib had become part of Türkiye’s security framework. The reportedly 20,000-strong Turkish military presence, like the Turkish observation posts, underlined this new reality.45 Moreover, the collapse of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s resistance in the face of government forces supported by their allies showed that without Turkish protection, even the strongest armed group in Idlib was no match for a concerted regime onslaught. Ankara’s intervention alone set the limits of the advancing Syrian forces, marking the canton’s contours and Türkiye’s security redlines.

TÜRKIYE BECOMES THE POLITICAL FOCUS IN THE CANTON

A second, fundamental characteristic of the northwestern canton is ingrained in its sociopolitical outlook. Until 2016, the numerous political actors who are now present in the northwest held a variety of political perspectives, with specific social forces supporting them. However, all were primarily focused on ousting the Assad regime from power in Damascus. In 2016, when toppling the regime was no longer a possibility, this situation changed. The northwest emerged as the last redoubt of these anti-regime groups, whose principal attribute was to become mainly local actors, albeit with different degrees of agency, helping to implement Türkiye’s political vision for the region.

In Idlib, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham has a near monopoly on power, while in Turkish-controlled areas, Türkiye’s military and political proxies, mostly former Free Syrian Army units and local councils, dominate security and governance. The latter are iterations of what had been labeled the moderate, Western-backed, or non-jihadi military and civilian opposition.

For the Syrian regime, these opposition movements in the northwest had emanated from Syria’s mostly rural conservative Sunni population, which was politically active and played a critical role in nurturing the rebellion against Assad’s rule. Not all inhabitants of the northwest were opponents of the regime, let alone politically committed. But the region did host a significant portion of what remained of the active groups and their social base that had sought to overthrow the Assad regime. A senior Syrian military officer privately described this population as “qanabel mawqutah,” or time bombs.46 In light of this, cantonization seemed to be an optimal regime approach for containing these people in the northwest. It also broke the momentum of their revolutionary political movements. If in 2012–2015 they were fighting to take Damascus, gradual cantonization changed the scope of their actions, turning them into caretakers of an impoverished “border nation” in Syria’s northwest.

This process was made possible between 2015 and 2018 by the Assad regime’s multiple evictions of defeated rebels and their families and supporters from other parts of Syria.47 The regime adopted a security approach, with no indication of wanting to engage in genuine national reconciliation. The populations of newly recaptured areas were essentially given two choices.48 They could either go through a security vetting process that entailed being cleared by the regime’s security bureaucracy. Those who were cleared either were displaced within regime areas or could go back to their areas of origin, while some were detained, tortured, or forcefully disappeared.49 The alternative was to accept expulsion to the northwest. Those not wanting to live under Assad rule were given the latitude to do so, with Russian guarantees.

Most people decided to remain in regime-held areas, while reportedly some 200,000 people from all over Syria were displaced mostly to the northwest.50 The regime was unprepared to reintegrate this recalcitrant population into the Syrian state, which only reinforced the northwest’s distinctive Sunni rural sociopolitical outlook, one that was uncompromisingly hostile to the regime, hence the expediency of their confinement in the northwest.51

The cantonization of the northwest also benefited Türkiye, albeit for different reasons. If the Syrian opposition was a threat to the Assad regime, it represented a valuable source of political capital for Türkiye. However, the displaced population, with its political groups, were not Turkish partners. Rather, they became local actors and proxies who helped Ankara stabilize the region, prevent a refugee influx into Türkiye, could be mobilized as a counterweight to the Kurdish population in northern Syria, and could even serve as bargaining chips in arrangements between Ankara and its Astana partners.52

For example, what remained of the Free Syrian Army, as well as other opposition groups, was restructured and renamed the Syrian National Army, under Turkish patronage.53 These groups were instrumental in Türkiye’s Olive Branch operation in Afrin in January 2018 and its Peace Spring operation in October–November 2019. Syrians even fought as mercenaries, with Turkish facilitation, in the conflicts in Libya and Azerbaijan.54 There was also population engineering. Some of those expelled from eastern Ghouta around Damascus, for instance, found new homes in Afrin after part of the local Kurdish population was displaced in the Olive Branch operation to Tell Rafaat and other adjacent towns under Syrian government and Russian control.55 The UN estimates that the Olive Branch operation displaced some 150,000 people from a historically Kurdish-dominated area.56

With respect to civilian governance, in the Turkish-controlled areas of the northwest this task has fallen largely on local councils, over which Türkiye has significant influence.57 In the early stages of the Syrian conflict, these councils were controlled by grassroots movements that focused on organizing protests, planning other forms of local mobilization, and documenting the war, before they shifted toward providing services.58 While these councils were, in theory, linked to the interim government of the Syrian opposition, in recent years they have become a facade for Turkish rule.59 Some reports in August 2023 in the Turkish media suggested that Ankara might appoint one governor to rule all the areas it controls in northern Syria.60 Today, the councils are dependent on outside aid—namely from Türkiye and some UN and nongovernmental organizations—and cannot sustain themselves independently. They remain focused on service provision and have no significant political role.61 However, through the services they provide, they are also crucial instruments allowing Türkiye to stabilize the region.62

The image is somewhat different in Idlib, where Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham has firm control and where Türkiye does not micromanage local affairs. Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham gradually consolidated its power by eliminating or incorporating other armed groups, notably the hitherto potent Ahrar al-Sham group. In November 2017, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham also formed the Salvation Government, which is dominated by the group and has ruled Idlib as a ministate.63 The Turkish presence on the ground introduced a degree of security to the canton starting from 2020, permitting Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham to make the area more stable.

A DEMOGRAPHIC DILEMMA

Cantonization was also a response to a larger demographic problem brought about by the war. During the early years of the conflict, moving through the Turkish border was relatively easy. This gradually changed starting in 2015 as the Turkish authorities tightened border controls and refused to take in more refugees.64 Concurrently, after the European migration crisis in 2015, Europe minimized its acceptance of refugees.65 With the Assad regime having no viable plan for reintegrating the population into the state, the northwest became a sealed haven for 4–4.5 million Syrians who, beginning in 2015–2016, had nowhere else to go.

In 2015, as Türkiye intensified its border controls, it left only two official border crossings open, and even these were accessible only to selected categories of people.66 Refugees continued to cross the border illegally until the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018, when many Turkish provinces stopped registering new asylum seekers to discourage trafficking.67 At the same time, Türkiye finished sealing its border with Syria by erecting a wall, the third longest after the Great Wall of China and the wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.68 By this time, Türkiye already was hosting some 3.5 million refugees.69 The turning point coincided with the European migration crisis, which was followed by a European Union-Türkiye deal in which Ankara agreed to prevent illegal migration to Europe in exchange for financial aid.70

The Assad regime, for its part, lacks the ability to reincorporate those living in the northwest into Syria because of the sheer effort that would be required to do so. Capturing those areas with its population would force Damascus to address a potentially severe security challenge, much along the lines of what is taking place today in southern Syria, which has yet to be stabilized five years after government forces took back the region.71 It would also represent a challenge for the resource-poor regime to provide basic services to those areas. In light of this, cantonization was the most viable alternative, even if it came at the cost of temporarily giving up some parts of Syria.

Neither Damascus nor Ankara is entirely satisfied with the situation today. The offensives by Syrian government forces between 2018 and 2020, for example, caused major displacement toward the Turkish border.72 The demographic outlook of the northwest could still be subjected to adjustments, traumatic ones in fact. For example, the Syrian regime, supported by Russia, still aims to implement earlier agreements reached in Astana between Russia and Türkiye on the one hand and Russia, Türkiye, and Iran on the other. These agreements stipulated that the M4 highway, which passes through Idlib as well as major rebel-held cities such as Ariha and Jisr al-Shoughour, should be open to transit traffic between regime-held Latakia and Aleppo. This issue has reportedly been discussed in a more recent Türkiye-Syria rapprochement process that began in December 2022 with Russian mediation.73 Though its implementation remains uncertain, if it is carried out in some form, it could cause yet another wave of displacement.

Turkish policies, too, could lead to major adjustments to the demographic outlook of the northwestern canton. The area has seen waves of forced displacements and demographic change, caused by all sides. If Türkiye remains true to its promise of repatriating Syrians to northwestern Syria in large numbers,74 this could significantly alter the area’s demography, given that the refugees in Türkiye are not necessarily from the northwest. This would amount to another crucial readjustment of the demographic character of the canton.

ECONOMIC OVERDEPENDENCY: BREATHING THROUGH THE BORDER

A fourth essential trait of the northwestern canton is its economic overdependency on Türkiye, including for aid delivery. The several crossings along the Syria-Türkiye border represent the economic lungs of the northwest. They enable the transit of goods into northern Syria, including from destinations worldwide, as well as the import of Turkish goods and services and the influx of humanitarian aid. Although there is some local production, the region would most certainly be choked economically without an open border.

In 2012, as war ravaged Aleppo, Syria’s northern administrative and economic capital, economic activities shifted to areas closer to the border, especially near border crossings. These areas were safer and became commercial and humanitarian hubs.75 This was the beginning of a new economic configuration in the north, one that focused on border areas and was reliant on them. The Bab al-Hawa crossing in particular became the most important artery connecting opposition-held areas with Türkiye and global markets.76

To put this in perspective, in 2010, when relations between Syria and Türkiye were still normal, Turkish imports to Syria, excluding smuggling, were valued at $1.84 billion.77 That figure dropped to $500,000 in 2012, before surpassing the prewar figure in 2014, when the value of Turkish imports reached $2.33 billion.78 Turkish goods were consumed locally or reexported to other areas in Syria. A Syrian researcher who visited the northwest in 2016 observed, “You cannot find a Syrian biscuit in Idlib anymore,” in reference to the dominance of Turkish goods in the market.79 In 2022, the value of Turkish imports remained around $2.23 billion.80 As the northwest does not have access to the sea, Türkiye’s port city of Mersin has been a transit point for goods arriving from across the globe before entering Syria.81

Türkiye’s successive incursions into northwestern Syria only integrated the region more into the Turkish economy. Gradually, Türkiye took over the provision of basic services, including education, healthcare, telecommunications links, and electricity.82 Despite Türkiye’s more limited role there, Idlib’s dependency has also increased since 2020. Fuel, for example, mostly enters from Türkiye, so that the interruption of fuel imports in June 2023 caused shortages due to the absence of alternative sources.83 Since May 2021, Turkish companies have also sold electricity in Idlib, underlining the increasing connectivity between Türkiye and the governorate.84

Humanitarian aid is another aspect of the region’s economy, underlining the importance of cross-border deliveries. At the beginning of the Syrian crisis, international humanitarian aid organizations operated out of Damascus. As the regime began losing control of large swaths of Syria, some aid organizations shifted their work near to opposition-held areas, setting up their operations across the border in Türkiye.85 Syrian organizations and relief networks became conduits for channeling this aid into Syria. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 2165 in July 2014 authorizing cross-border aid deliveries from several countries, including Türkiye, withoutthe Syrian government’s consent.86 The UN authorization was politically important, but in terms of scale, local, Turkish, and international aid organizations implemented most of the humanitarian response.87 In 2014, for example, the magnitude of aid provided by international nongovernmental organizations was around $400 million.88 This was vital for millions of people, especially those present in camps for internally displaced persons, but it also became a part of the local economy. In 2022, UN organizations, humanitarian agencies, and partners reached 2.7 million people in Syria every month through Türkiye.89

Besides the UN-authorized crossing, since its first military incursion in 2016, Türkiye has unilaterally reshaped its border with Syria by enlarging several border crossings in Jarablus and Al-Rai.90 Previously small, mostly civilian crossings have today become important passages for aid and commerce.91 That explains why any disruption or severing of those cross-border links would cause major disruptions to northwestern Syria.

While Türkiye has contributed to the transformation of the region’s economic outlook, the Assad regime, with the help of Russia, has repeatedly tried to deny resources, such as humanitarian aid, to the northwest or divert resources from there. The reason is that the regime was unhappy when the UN Security Council authorized UN and other humanitarian agencies to undertake cross-border operations from Türkiye into Syria, which denied Damascus the leverage to retain control over the distribution of aid. Damascus repeatedly protested this measure and insisted that all aid should continue to pass through the Syrian capital.92 Time and again, the issue of cross-border aid was debated in the UN Security Council, where Russia used its veto power to cut back on aid and channel it through Damascus.

In July 2020, Russia forced a Security Council resolution that reduced the number of UN crossings from Türkiye to one, namely Bab al-Hawa.93 In another move, in July 2022 Russia only agreed to six-month extensions of aid deliveries and insisted that some aid had to go through Damascus.94 In July 2023, Russia took things further when it vetoed a proposal to renew the cross-border mechanism for nine months and instead proposed a six-month extension, which was vetoed by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.95 A few days later, the Syrian government permitted the UN to use the Bab al-Hawa crossing without a Security Council resolution, on condition that aid delivery was “in full cooperation and coordination with the government.”96 UN and major donors rejected the offer.97

This latest episode demonstrates cantonization in action in northwestern Syria. Russia’s veto, like the regime’s proposal, showed how the parties were adjusting economic realities in the northwest by seeking to influence how aid entered the region, for whom, for how long, and under whose oversight. It showed how decisions by outside actors, in this case Russia and the government in Damascus, could distressingly modify the territory’s economic characteristics by severing or interrupting the aid flow to the destitute population in the area.

In sum, the northwest has evolved into a territory outside the Assad regime’s control and outside Syria’s national framework. It has instead become part of a supranational Turkish border security framework. The area assembles what remains of the political forces opposed to the regime, evolving in a space far from Damascus’ reach. Along the way, however, the northwest has lost much of its agency, becoming dependent on Ankara for its political, economic, and military survival. This ongoing cantonization process is unlikely to soon end.

Kaynak:Carnegie