Is Erdogan the Sick Man of Europe?

By Michael Rubin

For decades, beginning in the 19th century, Europeans referred to the Ottoman Empire as “the sick man of Europe.” First sultans and then so-called reformers acting in their names sought autocratic power. The Porte covered for a crumbling economy with grandiose projects and compensated for lack of popularity with disastrous foreign adventures. In its final decades, Turkish authorities played ethnic and sectarian communities off each other in order to consolidate power and ethnically cleanse Anatolia. Ultimately, the question diplomats asked during and after World War I was not if the Ottoman Empire would fall but when.

Turks like to embrace the glories of the Ottoman Empire at its peak, but shirk responsibility for its twilight years by arguing that Turkey was merely a successor state that emerged from a fractured empire, no different from Greece, Hungary or Syria. It is a useful formula to claim historical legitimacy but eschew responsibility for the Greek, Armenian and Assyrian genocides.

Today, history is repeating albeit on a smaller scale. Turkey may not be the sick man of Europe, but its dictator Recep Tayyip Erdogan is. Erdogan is literally sick, whether it is an epileptic fit in a locked armored car, a bout of colon cancer, or an apparent on-air heart attack. At 70 years old, Erdogan is still relatively young, but his vigor lags; he has repeatedly fallen asleep during televised speeches and state meetings. Erdogan’s aides may cover for him and his troll armies declare his bodily waste smells like roses but there is no hiding that, as with President Joe Biden in the United States, age has won over ambition. There is a reason why Erdogan increasingly promotes his son and son-in-law as each auditions to succeed him.

The sick man repeats history in other ways. Erdogan revives and relishes the Ottoman policy of genocide in both Turkey and Azerbaijan. As Erdogan continues to deny Armenian genocide from more than a century ago, he and his partner in crime Ilham Aliyev revive the Young Turks’ playbook. The opening salvo of the original Armenian genocide, for example, was the arrest of Armenian statesmen and intellectuals. This is why the imprisonment of Artsakh leaders following the Turkish-backed Azerbaijani invasion of the Armenian populated territory has been so chilling. Turkey’s continued blockade of Armenia proper violates the 1921 Treaty of Moscow.

Erdogan’s conversion of churches to mosques and his interference with Greek Orthodox property and seminaries inside Turkey is bad enough, but by interfering in the Greek community’s schooling inside Turkey, he gets in the way of the new generation maintaining their traditions and lifelong relationships that form the fabric of the community.

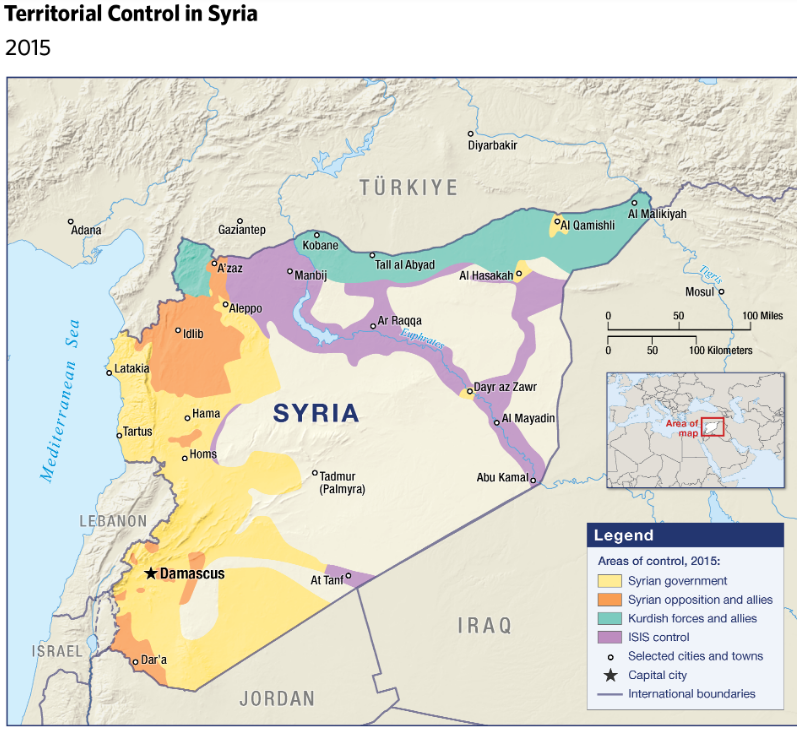

His targeting of Kurds and Yezidis replicates the strategy of Talaat Pasha against ethnic and sectarian minorities at the height of the genocide. During the original World War I-era genocide, Kurds stood largely immune because their identity at the time revolved more around religion than ethnicity. No longer. Today, Turkish security imprisons elected Kurdish leaders while the Turkish military’s drones and F-16s bomb Kurdish farmers and villages in Syria and Iraq. Most of the 2,000 Yezidis sold by the Islamic State who remain in captivity today reside as slaves inside Turkey.

Had Erdogan not failed academically as a student, he might understand that the “sick man” strategy he pursues today could destroy Turkey. Rather than preserve the Ottoman Empire, playing ethnicities off each other while holding Turks up as a privileged class exacerbated fault lines and led to the Ottoman Empire’s collapse.

As Ottoman authorities sought to cover their own financial incompetence, so too does Erdogan. Turkey today is insolvent. Reform was too little, too late. Erdogan can distract with Islamist rhetoric, anti-Semitism and ethnic hatred, but this does not save Turks from losing their savings to inflation.

As much as Erdogan embraces neo-Ottomanism, Turkey has permanently lost Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Bulgaria and Greece. Playing the ethnic and religious card inside Turkey, then, will only lead Turkey itself to fracture. Kurds react to repression not by forfeiting their identity, but by doubling down upon it. With every attack on Kurds, Erdogan ensures that Kurdistan will arise in eastern Anatolia. Just as dictatorships set Ethiopia and Sudan down the path to division, so too does Erdogan make Turkey’s collapse inevitable.

As Turks recognize Erdogan himself is the problem, he may find himself facing a Talaat Pasha precedent in another way, especially if his victims grow too impatient to outwait his current decline. Either way, Turks face an irony. As Erdogan talks about a two-state solution in Cyprus, his own legacy could very well be a two-state solution in Turkey.